Canadian Cannabis Prohibition Predated U.S. Ban by 15 Years

John Lennon and Yoko Ono with Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau in 1969 (Photo by Peter Bregg/The Canadian Press)

Canada’s path to cannabis prohibition closely followed that of its southern neighbor. Like in the United States, a century ago cannabis was widely available in tincture form as a medication before being banned in a campaign that blatantly harnessed racism and xenophobia. Yet now Canada is legalizing coast to coast, starting October 17, while the U.S. federal government refuses to end its 80-year policy.

The Anti-Immigrant Roots of Canadian Prohibition

The Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, the first major anti-drug legislation in the US, was passed on a wave of anti-Asian hysteria. In Canada, the connection was even more blatant.

On September 7, 1907, a thousands-strong white mob of the Asiatic Exclusion League rampaged through Vancouver’s Chinese and Japanese district trashing shops and throwing some immigrants in the harbor. “Not a Chinese window was missed,” it was reported.

Business owners demanded compensation, and the deputy labor minister—William Lyon Mackenzie King, who later as prime minister led Canada through World War II—was dispatched to investigate. King was shocked to find that the claimants included (legal) opium merchants. Back in Ottawa, he wrote a report on the opium menace, which warned that the Asian drug was catching on with white women and girls.

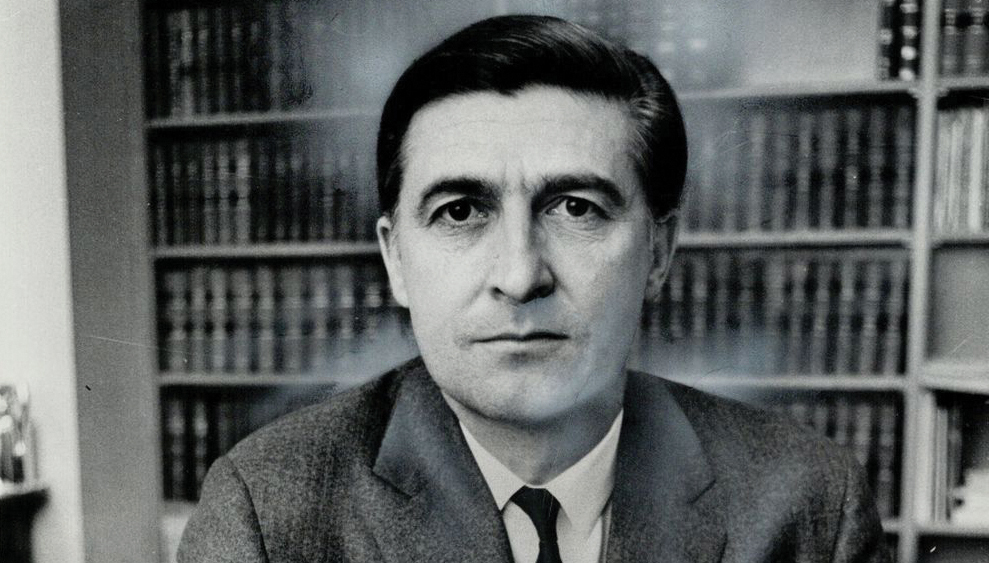

Former Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon MacKenzie King led the push to ban opium in 1908.

King subsequently drafted the Proprietary and Patent Medicine Act, effectively banning opium for all but restricted medical use. It passed in 1908 without debate. Morphine and cocaine were added to the law in 1911.

Marijuana’s turn came in the 1920s, a decade that saw a unified anti-drug and anti-Asian campaign. One commentary in the Vancouver Sun praised the Royal Canadian Mounted Police for “bending their energies to rid our Canadian soil of the Oriental filth of the drug traffic.” Canadian suffragette Emily Murphy wrote in Maclean’s of the “grave drug menace” posed by Asian immigrants plying “our children” with “poisoned lollypops.”

In 1922 and 1923, the drug laws were stiffened with penalties of summary deportation for foreigners found to have smuggled drugs. University of Guelph historian Catherine Carstairs (who wrote 2006’s Jailed for Possession: Illegal Drug Use, Regulation and Power in Canada, 1920-1961) reports that 671 Chinese immigrants were expelled over the next 10 years—most of them longtime Canadian residents. Hardly coincidentally, 1923 also saw passage of the Chinese Immigration Act, Canada’s equivalent of the United States’ Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. Apart from a very few students and merchants, Chinese immigrants were effectively banned from Canadian soil.

Also in that package of laws was a provision adding a new substance to the list of prohibited drugs: marijuana. This actually put Canada ahead of the U.S. when it came to cannabis prohibition. While a number of states had already outlawed it by then, the federal government didn’t act until 1937.

In 1922 and 1923, the drug laws were stiffened with penalties of summary deportation for foreigners found to have smuggled drugs.

“Whatever the motivation, marijuana was banned without debate,” Kate Allen wrote in the Toronto Star in 2002. “The only recorded statement in the House of Commons was: ‘There is a new drug on the schedule.’”

But there was little cannabis use to crack down on and annual convictions for marijuana over the next 20 years hovered between zero and 12. This changed quickly and dramatically some 40 years later with the counterculture eruption of the 1960s. As youth grew their hair long and grooved on the Beatles and homegrown Canadian talent like Neil Young, Joni Mitchell and the Guess Who, cannabis use suddenly exploded on college campuses and in hippie enclaves from Vancouver to Halifax. Conservatives were, of course, aghast and marijuana busts suddenly soared.

Former Canadian Supreme Court justice Gerald Le Dain’s commission called for marijuana decriminalization.

The Le Dain Commission Spoke Truth to Power

On May 29, 1969, Canada’s liberal prime minister Pierre Trudeau appointed the Royal Commission on the Non-Medical Use of Drugs to study the cannabis question. The commission was informally named for its chair, Gerald Le Dain, then dean of Osgood Hall, a Toronto law school, and later a Supreme Court justice.

As youth grew their hair long in the ’60s, cannabis use suddenly exploded on college campuses and in hippie enclaves from Vancouver to Halifax.

Looking at alcohol, LSD, opiates and barbiturates, as well as cannabis, the Le Dain Commission convened public hearings and heard testimony from thousands of people across the county, including John Lennon and Yoko Ono after their notorious “Bed-In for Peace” in Montreal. “This is the opportunity for Canada to lead the world,” the Beatle testified three days before Christmas in 1969.

The 320-page report, released in April 1970, determined that “cannabis has little acute physiological toxicity—sleep is the usual somatic consequence of over-dose. No deaths due directly to smoking or eating of cannabis have been documented and no reliable information exists regarding the lethal dose in humans.”

Calling cannabis penalties “grossly excessive,” the Le Dain Commission recommended decriminalizing personal possession of cannabis and drastically reducing the penalties for trafficking it.

It concluded that much of the scholarship around marijuana was “ill-documented and ambiguous, emotion-laden and incredibly biased . . . The resulting confusion is exemplified by current legislation in many parts of the world, including Canada and the United States, which classifies cannabis with the opiate narcotics, even though these drugs are pharmacologically different.”

In addition, the report noted, “Some observers have suggested that chronic smoking of cannabis might produce carcinogenic effects similar to those now attributed to the smoking of tobacco, although no evidence exists to support this view at this time.”

Calling cannabis penalties “grossly excessive,” the Le Dain Commission recommended decriminalizing personal possession of cannabis and drastically reducing the penalties for trafficking it.

Previous studies cited in the report—the British Indian Hemp Drugs Commission in 1894, the Panama Canal Zone Military Investigations into Marijuana carried out by the U.S. Army from 1916 to 1929, the La Guardia Committee’s report on «The Marihuana Problem in the City of New York» in 1944 and the Wootton Report on Cannabis again commissioned by Britain in 1968—had arrived at similar conclusions: a more tolerant and lenient approach to cannabis, as would the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse, chaired by former Pennsylvania Governor Raymond P. Shafer in 1972.

Posthumous Vindication for Le Dain

Canada initially failed to follow the Le Dain Commission’s recommendations. In the 40 years after the report was released, Canadian police forces recorded at least two million cannabis-related violations.

However, the commission’s findings would periodically be revisited. In 2002, “Cannabis: Our Opinion for a Canadian Public Policy,” a report by the Senate Special Committee on Illegal Drugs, stated, “The [Le Dain] Commission concluded that the criminalization of cannabis had no scientific basis. We confirm this conclusion and add that continued criminalization of cannabis remains unjustified based on scientific data on the danger it poses.”

Sadly, Gerald Le Dain died in 2007, before his work began to see fruit in public policy—apart from a national medical marijuana program unveiled in 2001. But with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, son of Pierre, now shepherding Canada’s Cannabis Act (C-45) into law, the courageous truth-telling jurist Le Dain has finally earned his vindication, albeit posthumously.

More Canada Coverage

The Meteoric Rise of Canada’s Legal Cannabis Industry

Provinces Take Lead in Canada’s Legalization Ramp-Up

The Top 12 Canadian Pot Stocks

This article appears in Issue 33. Subscribe to the magazine today!