A Brief History of Marihuana in Mexico

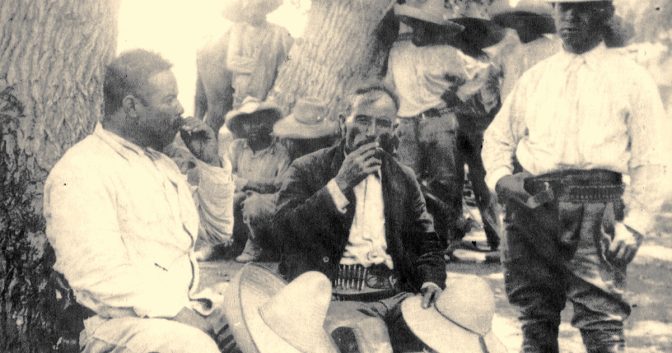

Pancho Villa (center) smokes a joint on his ranch in Chihuahua.

Mexico has been key in the worldwide spread of marijuana use and cannabis culture. It was through Mexico that the plant found its way to North America’s jazz vipers, beatniks and hippies. But the absurd policy of attempting to suppress cannabis in the same way as truly dangerous drugs like cocaine and heroin is a large part of what has propelled Mexico into a crisis of relentless, nightmarish narco-violence.

The legacy of the 500-year Moorish occupation of Spain was critical in Mexico’s rise as a global cannabis hub. The Moors brought hashish and the Maghrebi tradition of kif-smoking to Spain. It survived in the shadows among the Moriscos (crypto-Moors) even after the 1492 Catholic Reconquista and the Inquisition. Cannabis first entered the New World on Spanish galleons bound for New Spain (Mexico).

It caught on with both peasants and the higher classes in Mexico over the centuries. The iconic anthem of the Mexican Revolution, “La Cucaracha,” is about Pancho Villa’s peasant army getting high (“marihuana que fumar”) as they marched through the desert.

Mexico banned cannabis in 1920. When Harry J. Anslinger launched his successful campaign to have marijuana outlawed in the U.S. in the 1930s, demonizing Mexican immigrants was a decisive tactic.

In the 1960s, American hippies headed south of the border to Mexican states like Michoacán that grew large quantities of cheap mota. The explosion of cannabis use in those years prompted President Richard Nixon’s 1969 Operation Intercept, which paralyzed traffic at the border crossings with car searches for hidden stashes. This prompted diplomatic protests from Mexico. But in 1978, the DEA began aiding Mexican police by spraying pot crops with the defoliant paraquat.

Cannabis was how the notorious Mexican drug cartels got started. The embryonic cartels initially brokered exports for independent campesino (peasant) growers in Michoacán, taking the biggest share of the profits, of course. But they soon consolidated control, forcing small growers out of the export market. The new heartland of cultivation became the “Golden Triangle” in the remote, rugged Sierra Madre Occidental mountains, where the states of Chihuahua, Durango and Sinaloa meet. This territory is now virtually colonized by the crime lords, with the Tarahumara and Huichol Indians forced to grow cannabis (and now opium too).

When Harry J. Anslinger launched his successful campaign to have marijuana outlawed in the U.S. in the 1930s, demonizing Mexican immigrants was a decisive tactic.

As marijuana and opium production took hold in Mexico’s mountains, these criminal networks established themselves as middlemen for cocaine coming up from Colombia. The emergence of Mexico’s first narco syndicate, the Guadalajara cartel, was actually overseen by the Federal Security Directorate (DFS), Mexico’s answer to the CIA.

The role of the DFS in the Guadalajara cartel was revealed in Mexico’s press (some reporters paid with their lives) after DEA agent Kiki Camarena was tortured to death in 1985 on orders from the cartel’s co-founder Rafael Caro Quintero in retaliation for the bust of his huge marijuana plantation in Chihuahua. Caro Quintero was sentenced to 40 years after his capture, and spent 28 years in prison before he was released on a legal technicality in 2013.

Guadalajara cartel co-founder Rafael Caro Quintero

The Guadalajara cartel was eventually absorbed into the Tijuana cartel as newer, bigger cartels emerged in the border cities. Then, in the ’90s, the middle-level syndicates in Mexico’s interior began to revolt, demanding a bigger share of the pie. The most successful was the Sinaloa cartel, which started out as a satellite of the Tijuana cartel, but soon eclipsed it.

For Mexicans, the old cannabis heartland of Michoacán now evokes the severed heads left around the state as a warning by the cultish crime machine known as La Familia. Urban warfare in the border city of Matamoros, mass graves along the south bank of the Río Grande, and mutilated bodies left hanging from highway overpasses in Ciudad Juárez all reflect the grisly struggle for control of Mexico’s narco trade. Since 2006, when then President Felipe Calderón sent the army in to fight the cartels, an estimated 200,000 people have been killed. Mexico’s “drug war” became a real war.

The legacy of the 500-year Moorish occupation of Spain was critical in Mexico’s rise as a global cannabis hub.

While cannabis now plays third fiddle to cocaine smuggling and heroin production (with methamphetamine not far behind), it remains a significant factor in Mexico’s narco economy. That marijuana has come under the control of these ultraviolent criminal organizations is a bitter fruit of prohibition.

However, all this drug-related violence has sparked a reckoning. Ex-president Vicente Fox, who prosecuted the drug war aggressively while in power, has become an advocate for cannabis legalization. His successor, Calderón, signed a decriminalization law in 2009. While the maximum amount one can possess is five grams, activists are pressing to increase that, and also to expand the CBD-only medical-marijuana program that was launched last year.

It will take years to undo the damage wrought by prohibition in Mexico, even as cannabis-law reform moves in the right direction, albeit at the pace of a cockroach.

Related Articles

Vicente Fox’s Global Vision: Legalization of All Drugs

A $57 Billion Worldwide Cannabis Market by 2027?

Cannabis Law Reform Developments Around the World

80 Years of Reefer Madness (Part 1)